![]()

Content description

Use index notation with numbers to establish the index laws with positive integral indices and the zero index (ACMNA182)

Source: Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA)

Powers

When we multiply a number by itself, we usually use a more concise notation. For example:

| 3 = 3\(^1\) | (read as '3' or '3 to the power 1') |

| 3 × 3 = 3\(^2\) | (read as '3 squared') |

| 3 × 3 × 3 = 3\(^3\) | (read as '3 cubed') |

| 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 = 3\(^4\) | (read as '3 to the power 4' or as '3 to the 4th') |

| 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 = 3\(^5\) | (read as '3 to the power 5' or as '3 to the 5') |

| 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 = 3\(^6\) | (read as '3 to the power 6' or as '3 to the 6') |

The expression 3\(^5\) is called a power of 5.

The raised 5 in 3\(^5\) is called the index of the power.

The number 3 in 3\(^5\) is called the base of the power.

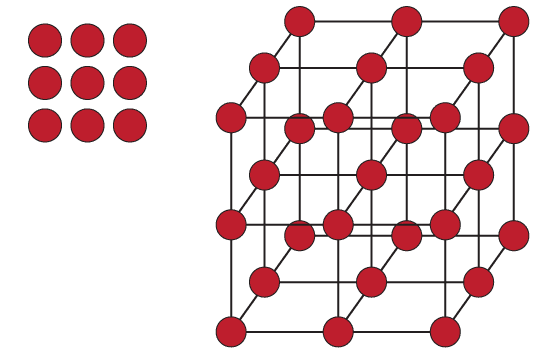

Geometrical representation of powers

The terms '3 squared' for \(3^2\) and '3 cubed' for \(3^3\) come from geometry. You might have seen \(3^2\) dots arranged in a square and \(3^3\) dots arranged in a cube:

The numbers \(0^2 = 0, 1^2 = 1, 2^2 = 4, 3^2 = 9\) … are called squares.

The numbers \(0^3 = 0, 1^3 = 1, 2^3 = 8, 3^3 = 27\) … are called cubes.

There is no straightforward geometrical representation of higher powers.